Although no state legislation is required to implement the GAP option under the Fostering Connections Act, some states have passed laws as a first step: Arkansas, Colorado, Michigan, New York, Texas, Vermont, and Washington. See sample legislation.

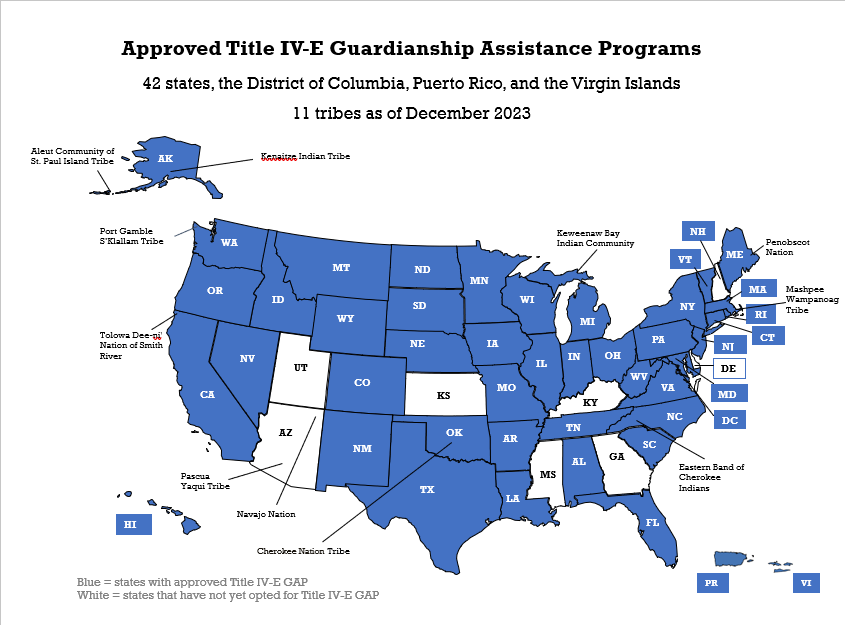

States, Tribes and Territories Approved to Operate GAP Programs

In order to take the option, states, tribes and territories are required to submit an amended Title IV-E Plan to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Children's Bureau for its approval. As of May 2023, forty-two states, the District of Columbia, eleven Tribes or Tribal Consortia, and Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands have obtained approval.

The eleven tribes are: the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island, the Cherokee Nation, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, Kenaitze Tribe, Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, the Navajo Nation, Penobscot Nation, Pascua Yaqui Tribe, Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, and Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation of Smith River, California (formerly Smith River Rancheria).

The forty-two states are: Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming

At least twenty-six of the states, and the District of Columbia, also allow children who are not Title IV-E eligible to exit foster care into subsidized permanent homes with relatives.[3] The jursidictions use their own funds to pay for these programs and can create their own eligbility criteria. For example, some choose not to require six months with the relative or do not require the relative to be licensed.

Most of the forty-one states and the District of Columbia approved to take the GAP option had state subsidized guardianship programs prior to the Fostering Connections Act and modified their existing programs to be able to use federal funds through Title IV-E, while keeping a state program for those children who are not IV-E eligbible. Some of the states that did not have state subsidized guardianship programs prior to taking the GAP option also enacted parallel programs for those children who are not IV-E eligible. One of the most recent states to add a parallel state program was Alabama.

Through a Program Instruction issued February 18, 2010, The Children’s Bureau at HHS has made clear that agencies can use the Title IV-E GAP funding for those children who were receiving guardianship assistance under state programs prior to the passage of the Fostering Connections Act, as long as those children meet the eligibility requirements of the Act.

Programs for Children Not in Foster Care

All of the these GAP programs and most state subsidized guardianship programs that preceded GAP are for children exiting foster care.[5]

The District of Columbia and Louisiana have state programs that do not require any type of current or past contact with the child welfare system or prior court involvement.[6]

The District of Columbia has what it calls a "Grandparent Caregivers Subsidy Program" for low-income caregivers who are not involved with the child welfare system. The latest information about that program can be found at http://cfsa.dc.gov/service/grandparent-program.

In 1999, Louisiana established its program known as the “Kinship Care Subsidy Program,” financed throught its state grant of federal TANF funds. Grandparents, step-grandparents or other adult relatives are eligible for an enhanced TANF payment --which is $100 more than the state's TANF child-only payment, but still roughly half of the state's foster care rate -- if they satisfy the following requirements: (1) possess or obtain within one year of certification, either legal custody or guardianship or provisional custody by mandate of the eligible child who is living in the home. Provisional custody by mandate is a notarized authorization made by the child´s parents to provide care, custody, and control of a minor childt; (2) have an income of less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level; (3) have neither of the parents living in the household; and (4) agree to pursue the enforcement of child support obligations against the parents.[7] For the most recent information about the program, see http://dcfs.louisiana.gov/index.cfm?md=pagebuilder&tmp=home&pid=466#undefined

Hopefully, with the growing success of GAP and lessons learned from the 55 jurisdictions that have taken the option, we will see more states and tribes provide financial assistance to grandfamilies outside the foster care system who obtain guardianship or legal custody of the children in their care. This type of preventative strategy helps prevent children from entering the foster care system in the first place.